Diversification away from China and its supply of critical minerals such as copper would put the global energy transition goals in jeopardy, analysts at Wood Mackenzie warned.

In a report this week, the firm warned that removing China from the world’s copper supply chain would create a $85 billion gap for Western economies to fill, which is says is a near-impossible task.

Copper is a crucial component of electrification; without it, the world cannot decarbonize. WoodMac estimates that demand for the metal is set to rise as much as 75% to 56 million tonnes by 2050.

Meeting this demand won’t be easy.

Existing mines and projects under construction are expected to meet only 80% of copper needs by 2030, the International Energy Agency has said.

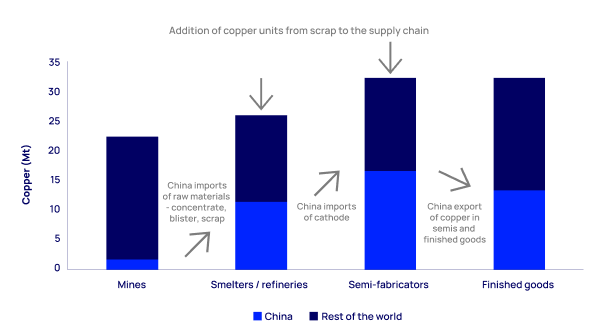

However, supply growth is more than just about building new mines. Downstream processing (smelting and refining) and semi-manufacturing/fabricating are also major parts of the copper supply that WoodMac analysts say are being overlooked.

Currently, China dominates both of these sectors.

China’s dominance

WoodMac estimates that close to 80% of copper mining produces copper concentrate, which must then be processed at smelters and refineries to produce the copper cathode traded in terminal markets.

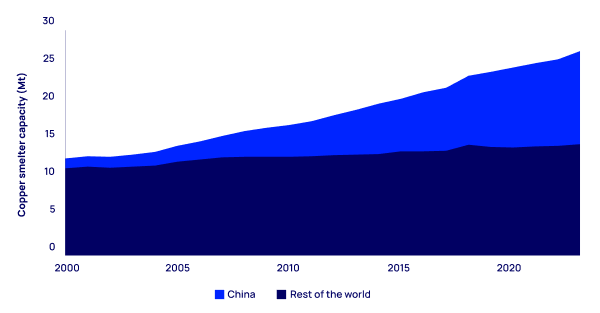

Since 2000, China has accounted for 75% of global smelter capacity growth and currently controls nearly all of global smelting and refining capacity (97%), contributing over 3 million tonnes of production and nearly $25 billion in investment, it says.

The country has also added nearly 11 million tonnes of copper and alloy capacity since 2019, representing around 80% of global additions. Approximately two-thirds of these facilities produce wire rods, giving China half of the world’s fabrication capacity, with further expansion underway.

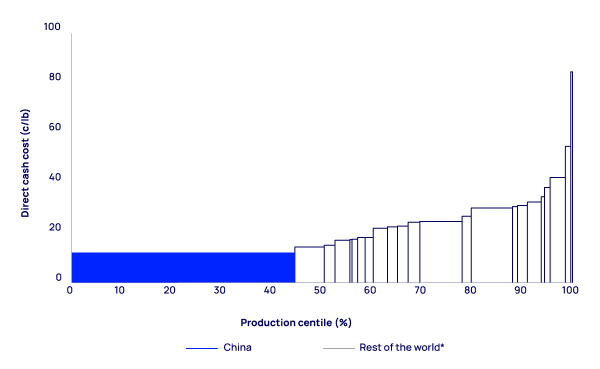

“China’s copper smelting industry has undergone significant evolution,” commented Zhifei Liu, managing consultant, copper markets, at WoodMac. “In the 2000s, a drive for stricter environmental and efficiency standards led to the modernization of smelting capabilities.

“Today, Chinese smelters are low cost and meet high environmental standards, particularly in sulphur dioxide capture, making them highly competitive.”

Meanwhile, semi-fabricators outside of China are facing challenges due to lower utilization and higher operating costs despite efforts like the Inflation Reduction Act, and there are no plans for new primary smelting capacities in North America or Europe, WoodMac’s report says.

Life without China

Without China, whose first use of copper accounts for 50% of global demand, it is expected that significantly more processing capacity would be required to meet energy transition targets.

WoodMac estimates around 8.6 million tonnes of additional copper demand ex-China over the next decade, driven by growth in transport, power and electrical networks. This equates to 70% of smelter capability and 55% of fabricator capacity in the rest of the world.

Assuming global average capital intensity, nearly $85 billion in new smelting and refining capability would be needed to displace Chinese supply, it adds.

Yet, as the WoodMac report points out, capacity has barely changed outside China over the last 20 years, raising the question of whether such a shift is achievable.

A scenario without China for the copper supply chain, says Nick Pickens, WoodMac’s research director of global mining, would require “a substantial increase in processing capacity to meet energy transition targets.”

Compromise needed

While copper supply risks can be mitigated and some rebalancing has begun in various countries, the scale of China’s dominance in the supply chain means “complete replacement is unfeasible,” Pickens goes on to say.

He also notes that the introduction of new processing and fabrication facilities may result in higher costs and delays in the energy transition. “Financing these investments presents additional hurdles, with resistance to new smelter projects on environmental and social grounds particularly strong in Europe.”

Unless there is a seismic shift in the rate and efficiency at which the rest of the world deploys capital and operates, decoupling from China completely will mean a more expensive and much slower energy transition, the report says.

To conclude, pragmatism and compromise must be considered to achieve net zero goals, according to WoodMac.