Although electric cars haven’t quite taken off in the 2010s the way some had anticipated, sheer economics are pointing to the 2020s as the time when EVs will find that market fever pitch.

From 2010 to 2019, lithium-ion battery prices (when looking at the battery pack as a whole) have fallen from $1,100 per kilowatt-hour to $156/kwh—an 87% cut. From 2018 to 2019 alone, that represents a cut of 13%.

Those numbers were part of an annual report released Tuesday by Bloomberg New Energy Finance (BNEF). The report also suggested that we’ll reach the $100/kwh mark earlier than it had previously anticipated—by 2023.

A battery pack is typically the single most expensive component in an electric car. While automakers have so far decided to add more cell capacity into their vehicles as the price falls, the potential is there as infrastructure builds out for dramatically more affordable models that go modest on battery capacity.

Just two years ago, in 2017, the average price of a lithium-ion vehicle battery pack was $209/kwh, and BNEF had previously predicted the business would fall below $100/kwh by 2025.

Why will that point come sooner than previously estimated? Part of it is that the size of battery orders has become larger—underscoring a vote of confidence on behalf of automakers that the global market for electric vehicles will keep building.

BNEF now anticipates that pack-based cell prices will dip below the $100/kwh mark in 2024. It sees a continued reduction of cell prices leading to a projected $61/kwh by 2030, although it notes much greater uncertainty with the latter target.

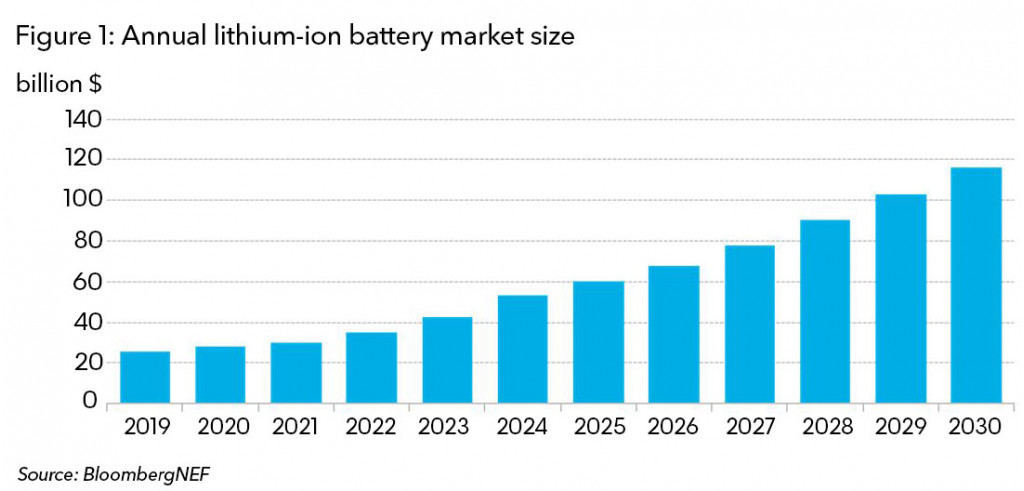

James Frith, the senior energy storage analyst who authored this report, said that BNEF estimates the size of the global battery market to be $116 billion annually, not including investment in the supply chain. “However, as cell and pack prices are falling, purchasers will get more value for their money than they do today,” he underscored..

As automakers simplify electric vehicle design to become based on standardized cells and modules that can be scaled up or down within platforms—like Volkswagen’s MEB achitecture—some of the ancillary pieces like cooling can also be standardized and made more affordable.

Lithium-ion market size – BNEF, 2019

Factory and manufacturing costs are falling in the early part of the decade, too, and adding to that better-than-anticipated affordability. To reduce transportation costs (and potentially avoid import duties), more battery manufacturers are building plants on a region-by-region basis. SK Innovation, for instance, is building a plant in Georgia that will supply VW’s electric-vehicle manufacturing in Tennessee, while LG Chem and GM just announced a joint-venture plant in Ohio. And Chinese battery giant CATL has said that it’s considering a U.S. location.

In the second part of the decade, the gains may be less from scaling up and standardizing, and more from expansions of existing facilities, improvements in manufacturing equipment, and materials-related improvements.

The continued downward trajectory in cell prices has wide-ranging effects that go beyond passenger vehicles. It’s making it more attractive to electrify commercial delivery vehicles, BNEF points out.

Within these cost declines, automakers may soon face new choices, the firm anticipates—between attributes like a longer cycle life versus a cheaper cost. Which could potentially, when high-capacity batteries are as ubiquitous as affordable storage media today, establish another fine point to what separates a premium car from the rest.