100 million. It’s a number that drowns comprehension; it’s more jelly beans than can fit in an average-sized swimming pool.

Within a year, world oil consumption will top 100 million barrels of oil per day. Over the same time period, close to 100 million new piston-firing vehicles will be bought by petroleum-thirsty customers.

I hate to say it, but any notion of imminent “energy transition” or “decarbonization” is folly.

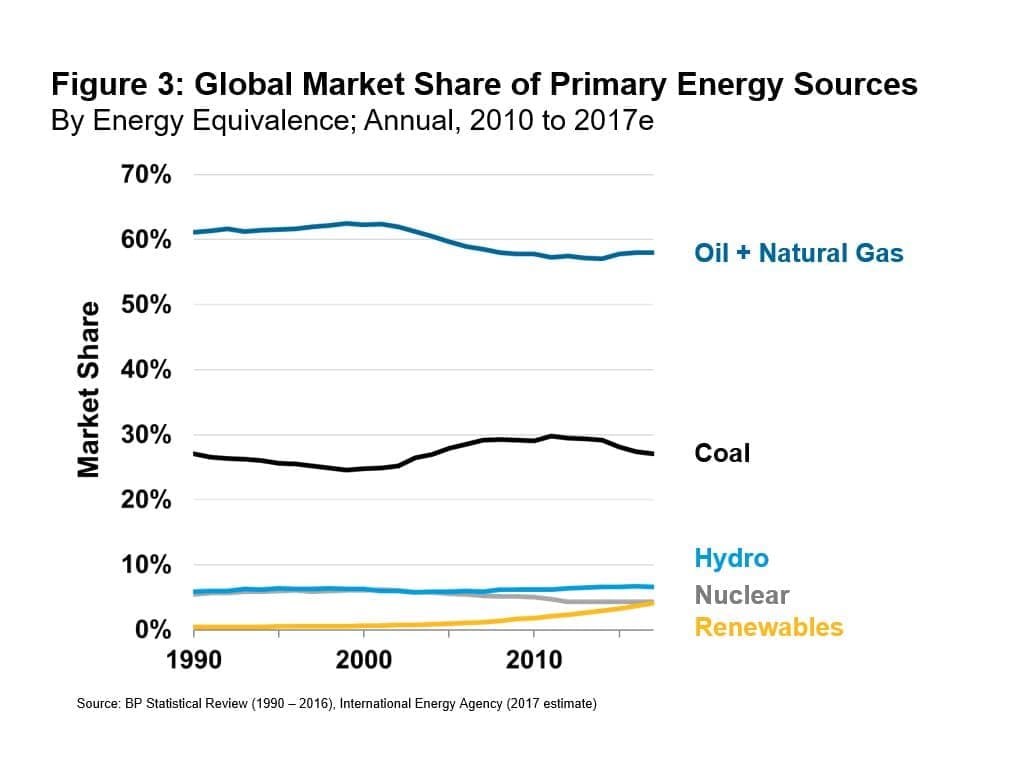

In fact, the percentage of fossil fuels in the world’s energy mix—coal, oil and natural gas—is still lingering well above 80 percent, a figure that has changed little in 30 years. That remains so, despite being challenged by serious environmental policies, financial pressures, viable alternative systems, public awareness and social activism.

It’s true that wind and solar are being deployed quickly, at an exponential rate in fact. But impressive as it all is, renewable energy installations are far too slow to catch the still-hardy appetite for fossil fuel consumption. Such energy obesity is not virtuous, but it’s a fact needing acknowledgement in a world of over seven billion people, each of whom are wanting for more light, heat, mobility and a panoply of mostly useless gadgetry.

Oil and gas are growing especially fast. Recently published data reminds us that we’re consuming hydrocarbons faster than ever, at robust rates on a global absolute basis (see Figure 1). Market share for oil and gas is holding steady at just under 60 percent.

The resilience of fossil fuels is sobering, even after massive capital assault.

Over the past decade, the world has spent US$ 3.0 trillion on renewable energy, according to the International Energy Agency (Figure 2). For that expenditure, the clean cadre has taken a couple of points of share away from coal, the black stuff that seems to have nine lives (Figure 3).

That’s a pricy calculus to date: some trillion-and-a-half dollars has been the ticket to steal only a percentage point of market share from an easy, reviled target.

It’s true: The price of renewable energy and electric energy storage is coming down quickly. Such new technologies are a marvel, in fact a necessity for the future. So, maybe the next trillion dollars of capital will buy more market share than just faint chatter on a chart.

Meaningful “transitions” occur when new offerings handily clobber the installed user base. When calculators came to market the use of slide rules went into rapid demise. In the world of energy, where renewables and electric vehicles are the new entrants, it is as if calculators are coming to market, but slide rule sales are increasing their presence too.

For now, we’re in an era of “energy diversification,” where alternative sources to fossil fuels, notably renewables, are growing alongside—not at the expense of—the incumbents.

In large part, the rigidity of the establishment is because the long-term cost of bringing a Joule of energy to consumers, from every source and system, is falling. And in western economies energy producers of all types are innovating to reduce their environmental footprint and make their products cleaner too.

Over the past few years, there has been growing acceptance of a narrative that I call Plan A: “Technology will facilitate the rapid demise of fossil fuels.”

Plan A is not working, because all systems, including fossil fuels, can deploy technology and compete to assault or defend market share.

Yet, crossing the 100 million thresholds of anything has a worrying air of unsustainability. So, a new plan is needed, one that doesn’t rely on overzealous polarization of energy systems and the naivety of thinking that energy transitions are as simple as pitching out a slide rule.

We need Plan B, a narrative that accepts the difficulty of change in energy markets. It’s a plan that doesn’t confuse market share with sustainability and reducing emissions. It’s a plan that is inclusive, collaborative and recognizes that: “All diverse energy types and stakeholders must be part of the solution.”